As a quick review of

Part I, I went over five of the seven criteria I use to evaluate board games. This is a scale with a maximum score of five broken down by the following categories:

Originality (0 - 1 pt) - How exciting is the unique combination of ideas that bring this game off the shelf? Does it stand out from similar games?

Theme (0 - 0.5 pt) - Do the thematic elements blend into the game play? Is the theme fitting? Does it increase my interest in playing or is it a last minute addition?

Pure Fun (0 - 1 pt) - Do I enjoy the game? Is it a go to game when I have the necessary player count? Does the game play move along or does it often move too slow?

"Re-play-ability" (0 - 1 pt) - Do I feel the need to revisit it in order to try new options and strategies? Is it predictable? Do I want to play again immediately?

Strategy to Luck Ratio (0 - 0.5 pt) - Does the game present itself well as far as the impact of strategy vs. luck? Is the amount of "luck" adequate for the game length?

Now the final two categories:

Player Scaling (Up to 0.5 pt)

Player Scaling (Up to 0.5 pt)

When I'm looking to acquire a new game one of the first items I look at is the intended number of players. 2-4 is limiting when you've game nights of five or six people.

There are fun party games that are 4-8+ but they really mean 7+ for an ideal experience. Games that have 2-6 or 3-5 often really need the upper end of the range to put all the player actions or roles into play or the lower end of the spectrum as additional players largely only add time with little to no additional player interaction.

This is a measure of how viable it is to get to the table, a larger "optimal" player range, the better the game under this rating. Two player games do get a pass here unless they are functionally broken. There are no bonus points but I do enjoy when games have different pacing or alternate strategies emerge as more viable with different player counts with the same game. Tongiaki is almost a completely different game when played with two players versus six players.

0.5 - Small World, Wits & Wagers, Coloretto

0.25 - Around the World in 80 Days, Scotland Yard

0.0 - Blokus, Citadels

Parity (Up to 0.5 pt)

This final category is mostly about ensuring there is tension in a game. As I've mentioned in a

previous article about final scoring, it is often the final controllable factor of whether the designed experience was enjoyable or not. Scoring shouldn't have a runaway leader problem nor should it transmit to a beginner that twenty minutes in that they are in for the long haul with no shot at the podium.

I have no qualms with defeat normally but if the session commonly turns into "I gotta catch Bill as he rolled three sixes to start" for an hour I have an issue.

Games that have an all or nothing achievement, such as conquering the globe in Risk or bankrupting everyone else in Monopoly, can leave players slightly jaded at the end as one person comes out with a glorious victory while at least several others were more witnesses or victims than participants . This is a negative in my book as it doesn't leave others with a sense of "what if?" that motivates them the next time, a thought of "I see I could have done this for four more points and that for three more that may have been the difference."

0.5 - Transamerica, In the Year of the Dragon, End of the Triumvirate

0.25 - Kahuna, Jambo, Rosenkonig

0.0 - Risk, Jenga, Monopoly

|

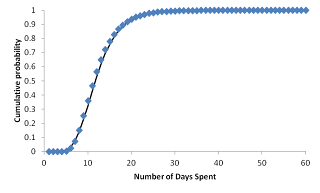

| My BGG ratings distribution |

Games Rated

Now the criticisms are fair; I don't exactly follow the standard BGG.com "recommended rating" method and on rare occasions I've received messages that respectfully disagree with my personal rating system, but it does have its own argument to make. Lets look at several examples:

La Citta

Originality (

1.0/1.0) - Great blend of mechanics

Theme (

0.5/0.5) - Region-building at its best

Pure Fun (

1.0/1.0) - Controlling a "mega-city" feels powerful

"Re-play-ability" (

1.0/1.0) - Many interesting decisions

Strategy/Luck Ratio (

0.5/0.5) - Randomness can be mitigated

Player Scaling (

0.5/0.5) - 2-player is fine, Excellent with 3-5

Parity (

0.5/0.5) - Runaway victories do occur, but rarely

Overall 5.0/5.0 =

10 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

10 - Outstanding. Always want to play and expect this will never change.

My Rating:

This is of course very fitting as one of my few perfect tens. It holds a special position on the shelf.

Power Grid

Originality (

0.75/1.0) - Mechanics mesh well, little innovation

Theme (

0.5/0.5) - Plays like I'm supplying energy to cities

Pure Fun (

0.75/1.0) - Decisions can get bogged down at times

"Re-play-ability" (

0.5/1.0) - Game length a hindrance

Strategy/Luck Ratio (

0.5/0.5) - Strategy is strongly rewarded

Player Scaling (

0.5/0.5) - Neat intricacies between player counts

Parity (

0.5/0.5) - Feels close throughout, strong catch-up mechanic

My Rating:

Overall 4.0/5.0 =

8 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

8 - "Very Good Game. I like to play. Probably I'll suggest it and will never turn down a game."

While Power Grid is a very good game, I'd certainly turn it down if two good shorter games were an alternative. I enjoy playing but there are many games I'd suggest over it, some being rated lower than Power Grid but play much faster.

Ticket to Ride

Originality (

0.75/1.0) - Love the mechanics, but very simple

Theme (

0.5/0.5) - Solid theme

Pure Fun (

0.75/1.0) - Very enjoyable game for its length

"Re-play-ability" (

0.5/1.0) - Initial intrigue is short lived

Strategy/Luck Ratio (

0.5/0.5) - Great strategy/luck mix

Player Scaling (

0.25/0.5) - Race with 2 and logjam with 5

Parity (

0.25/0.5) - One player can go unchecked too often

My Rating:

Overall 3.5/5.0 =

7 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

7 - "Good game, usually willing to play."

I would say my feelings about Ticket to Ride match the BGG recommended rating. It is a good game and I'd usually be willing to play, it does need some variety periodically to keep it from getting stale.

Blokus

Originality (

0.75/1.0) - Not much like it

Theme (

0.0/0.5) - Abstract. Fun, but still an abstract.

Pure Fun (

0.5/1.0) - My enthusiasm is weakening

"Re-play-ability" (

0.5/1.0) - Little variety between games

Strategy/Luck Ratio (

0.5/0.5) - Perfect information

Player Scaling (

0.0/0.5) - Purely designed for 4

Parity (

0.25/0.5) - If everyone comes your way- you're done

My Rating:

Overall 2.5/5.0 =

5 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

5 - "Average game, slightly boring, take it or leave it."

I probably feel a little more fervor about Blokus than one may think from this rating but that is because it suffers in getting to the table. With 4 players being optimal player count, it brings a competitive field of games for 4 players that have more depth and intrigue. It loses out as an abstract, but overall I probably enjoy this game at about a 5.5 or 6.0 level.

Saint Petersburg

Originality (

0.5/1.0) - Ahead of its time, similar games are superior

Theme (

0.0/0.5) - I just don't feel it, could have been any theme

Pure Fun (

0.25/1.0) - Theme probably carries over here, feels stale

Replayability (

0.25/1.0) - Repetitive and cumbersome

Strategy/Luck Ratio (

0.25/0.5) - Interesting decisions rarely show

Scalability (

0.5/0.5) - Works nicely with 2, 3 & 4 Players

Parity (

0.0/0.5) - Arguable, but I see too many blowouts

Overall 1.75/5.0 =

3.5 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

Somewhere between:

3 - "Likely won't play this again although could be convinced. Bad." and

4 - "Not so good, it doesn't get me but could be talked into it on occasion."

I fall right between these two descriptions as it has never been a game I've particularly enjoyed and if given nearly any other option I'd probably elect it over this. I should clarify, this is not a bad game at all though, very functional and sound design for what it is intended to do, it just doesn't captivate my interests.

Conclusion

Imperial

Originality (

1.0/1.0) - A true pioneer in many ways

Theme (0.5/0.5) - I'll give it the benefit of the doubt

Pure Fun (0.75/1.0) - The fun value has decreased

"Re-play-ability" (0.75/1.0) - The excitement has faded

Strategy/Luck Ratio (0.5/0.5) - No luck

Player Scaling (0.5/0.5) - An interesting experience with each player count

Parity (0.5/0.5) - With plenty of common property, its hard to break free

Overall 4.5/5.0 = 9 out of 10

BGG Recommended Rating:

9 - "Excellent game. Always want to play it."

As I mentioned briefly in the intro, I've recently come to terms with a loss of affection for Imperial. It has served its purpose masterfully, but I no longer reach for it at each gaming opportunity. Underneath the investment wargame fasade exists an investment game that uses war to determine the market valuations. Imperial isn't enough of an investment game for the time it takes to play it, and the military actions literally go around in a circle and have begun to feel like a chore. I hope to get Imperial back to the table several times this year and re-evaluate, but for now it is trending downward.

Now in hindsight it seems kind of silly to write two articles over lowering a game rating by 10%, but I'm done and I need to go start my taxes now. Thanks for reading.