My third and (for now) final follow-up to the game ratings scheme I published a few weeks ago deals with the aesthetics of abstract games. Alex touched on the topic when he discussed approachability, citing the relative simplicity of the rules of chess as part of its beauty. My friend and fellow gamer Josh agrees and puts it more strongly: "abstract aesthetics [like those in] chess should not necessarily be a detractor; I think chess can, in its own way, be very beautiful."

I defined "aesthetics" as a (mostly arbitrary) combination of a game's sensory elements--typically visual and tactile--and its theme. It's tempting to sub-divide the aesthetics score into "sensory" and "thematic" sub-scores, awarding perhaps up to one point for each, to better describe the contribution of each to the game's overall aesthetics.

But I deliberately avoided that level of granularity. It's useful to take a more holistic approach to evaluating aesthetic quality because there's also an implication of integration between the two: the visual

design should reflect the theme (the mechanics should too, but that's a

more complicated consideration). And sensory and thematic design are in that statistical murky ground of being neither perfectly correlated nor truly independent.

Based on the way I've defined aesthetics, a game needs both an attractive sensory design and a compelling theme to earn a high aesthetics score. It would be tough to argue that chess has a compelling theme because it doesn't have one at all--it's entirely abstract. But that doesn't necessarily mean that it has no sensory appeal. As both Alex and Josh both point out, plenty of people find chess not only visually pleasing but among the most beautiful board games that exist, precisely because of its iconic abstractness.

Since this blog is focused on important considerations for game design, what are the takeaways from trying to evaluate the aesthetics of abstract games? First, it's a much tougher task than it appears at first, and in many respects, appropriately evaluating aesthetics becomes tougher as a game becomes more abstract. In a strongly themed game, it's relatively easy to determine how well the visuals fit the theme. In abstracts, particularly the "classic" abstracts, that determination becomes a trickier--and more subjective--proposition.

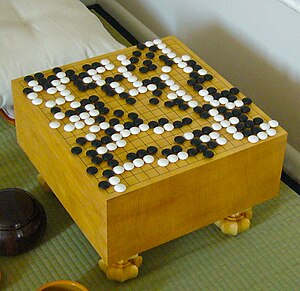

A related point: only a few games flourish as complete abstracts. Chess and go and backgammon have been immensely popular for centuries, but that continued popularity shouldn't give contemporary game designers incentive to avoid the responsibility of coming up with a suitable theme for their games. As this blog has discussed before, a theme is an essential component of developing and marketing a game successfully.

Finally, the prospect of applying a contemporary rating scale to a classic abstract might involve faulty logic on its face. Modern games are often the product of a single designer or team of designers, while the much older games are products of hundreds of years of cumulative development. Chess has apparently been played in Europe since the 1200s, while its rules weren't finalized until the 19th century; Go took more than a thousand years to become the game played today. What does that mean for contemporary game design? Avoid drawing comparisons to classic games, because they've had centuries of playtesting that you haven't.

So was I incorrect in using "completely abstract" as reasoning for giving a "0.0" aesthetics score? I don't think so, but I think I erred in picking chess as the "complete abstract" to illustrate the point. The real lesson here is how difficult it is to use such a well-known and immensely popular game as a basis of comparison. In his rating scale, Alex stipulates that he doesn't rate games played with an ordinary deck of cards because a from-scratch game is necessarily a better design achievement than one used with standard cards. I still believe that, all else being equal, a themed game is necessarily a better design achievement than a pure abstract, but in the future, there's wisdom in avoiding the traditional abstracts as bases for comparison.

No comments:

Post a Comment