Fresh off a successful Kickstarter campaign, the Fate of the Norns RPG system is gearing up to release its core rulebook. In advance of it, the guys behind Fate of the Norns put out a quick mid-level adventure showcasing the system, which my friend Joe picked up and started running. We had our first session yesterday, and it seems promising so far.

Fresh off a successful Kickstarter campaign, the Fate of the Norns RPG system is gearing up to release its core rulebook. In advance of it, the guys behind Fate of the Norns put out a quick mid-level adventure showcasing the system, which my friend Joe picked up and started running. We had our first session yesterday, and it seems promising so far.Character Creation

The Fafnir's Treasure module included pre-generated characters--and the core rulebooks that describe how to make a character don't seem to exist yet--so we didn't get much experience with character creation. Each of the pre-gens came with six combat attack powers, six allocated skill ranks, and a handful of passive abilities. Presumably, during actual character creation, you could choose which combat powers or skills you character was trained in. Because the characters started at level 10 (where a commoner might be level 1, and an important figure in town might be level 5), they were a little complicated to understand at first, and without seeing the underlying mechanics, it was impossible to figure out exactly how level affects a character's abilities.

One choice we did get to make was the "Void Rune" power, which is a lot like a theme in D&D 4th Edition. It gives a character one additional combat power and one additional skill training, plus it binds your character to either the Physical, Mental, or Spiritual attribute. Interestingly, unlike in virtually every RPG system out there, there are no ability scores, only skill trainings and the Void Rune binding.

Core Mechanics

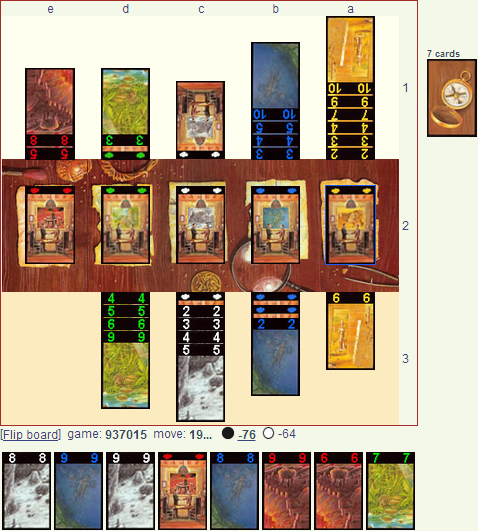

Another huge departure from tabletop RPG convention is a complete lack of dice. Instead of making checks (as in D&D) or building dice pools (as in Burning Wheel or a host of other d6 games), whenever a task is attempted, a character casts his runes. drawing a certain number of marked tokens from a pool. (With the 10th level characters, that number, called Destiny, was 2; it presumably increases with level.) For each token that matches the attribute that the GM determines, the character logs a success, with an automatic success granted for the Void Rune's binding and for skill ranks.

For example. say a character wanted to interpret an omen. The GM might say to test Spirit against difficulty 3. The character's Void Rune is bound to Spirit (1 automatic success), he is trained in Omens and Portents (1 automatic success), and he draws one Physical rune (nothing) and one Spiritual rune (1 success). The character passes the test and is able to interpret the omen correctly. Whether intentionally or not, the system mimics that of D&D Next in that it decouples stats from skills--a GM could just as easily call for a Mental test to read the omen, and a character would still be able to apply the skill training--and it makes skill training valuable in that automatic successes are very powerful.

Combat

With no dice, combat becomes a lot more about doing things than trying to do them. It can be a welcome change from a system like D&D, where between one third and one half of your actions are wasted because of poor die rolls. At the start of each round of combat, each character's runes are cast, determining which abilities can be used that round. Limiting which abilities are available in a given round is a bit of a two-edged sword: it cuts down analysis paralysis at the expense of reducing a player's ability to plan his character's turn ahead of time.

One of the more innovative elements of combat in Fate of the Norns is the option to attach runes to others and create "rune chains". Depending on the power, a rune chain might allow a power to affect more targets or ones farther away, to increase its damage, or to maintain it beyond the current round. The rules are still a little rough, so it's occasionally difficult to determine the proper application of these "meta tags," but it's a neat mechanic that gives a productive out to an otherwise-useless ability. Having no dice to dictate "misses," extra runes can also be expended to defend against attacks.

When you do get hit, your runes start slowly migrating towards death, meaning that your combat effectiveness decreases once you've been wounded a lot. It's a system that lots of D&D house rules have tried to implement, mostly unsuccessfully, but that feels natural and intuitive here. The game's "difficulty" can be adjusted on the fly by changing the number of spaces on a character's wounds must progress before dropping into the "death" zone.

Fate of the Norns uses a hex grid battle mat. It's my first experience with a hex grid system, and frankly, it makes a lot more sense than the square approach favored by recent editions of D&D, fixing the diagonal problems of 3rd Edition (too much math) and 4th Edition (unrealistic geometry).

Flavor and Roleplaying

Nordic, Viking-flavored games are easy sells, and rightly so. Sagas of adventure, iconic monsters, and epic conflicts permeate the mythos, making an ideal setting for a roleplaying game. We haven't gotten into--and probably won't get much into--advancement or getting too deeply invested in the game world, which is fine for a one-off adventure but a critical part of a more fleshed-out roleplaying system. The description of the Nordic archetype for each character is nice, giving at least a glimmer of personality to get you started, plus giving each character a clear lineage from the myths.

Bottom Line

Fate of the Norns still has some work to do. Even beyond the absent character creation and advancement rules, the rules are inconsistent in a few places and undefined in others--for example, there appear to be no rules for suffering wounds outside of combat, and it's completely unclear how long certain effects last in battle. But those rough patches aren't unexpected given that Fafnir's Treasure is essentially an open beta for the system.

The runecasting mechanic is novel if nothing else, but at least at first glance, it seems plenty capable of supporting a full-fledged roleplaying system every bit as well as dice. Expending unused runes to perform miscellaneous actions or to enhance attacks in combat takes some getting used to at first but ends up working smoothly and logically. Skill tests seem unnecessarily subject to variance since every rune drawn gives only a 1/3 chance of success, but the bright side is that your character really does excel at thing she's trained in.

I'm looking forward to playing through the rest of Fafnir's Treasure; if the system continues to hold up after a few sessions (and if the core rulebook ever actually shows up), it would be interesting to delve deeper into character creation and customization. The group I played with consists of four veteran gamers, and we picked up the rules in about half an hour--it's not the elegant simplicity of "roll a twenty-sided die and add a number to it," but it came together reasonably quickly, it was easy to get excited about, and I enjoyed my first session with the game enough to at least see what else it can do.